The Second Vatican Council marks a hiatus in the history of the Roman Catholic Church. The first document to be formally approved by the Council, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, opened the door for the liturgical use of local languages in the place of Latin. What was believed at the time to be a strictly limited departure in pastoral contexts led only a few years later to a disturbing new Order of the Mass. At the same time, for all the protestations of fidelity to Tradition, shifts in theology led to the propagation of new conceptions of the Church and of the Christian Faith. For some, the Council brought reforms long overdue. For others, it opened the way for an unconscionable revolution.

Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome

The venue for the Second Vatican Council

Strange as it may seem, the busy, idealistic work of coming up to date, the ‘aggiornamento’ called for by Pope John XXIII, had an unlikely precursor in the manoeuvering of the anti-Catholic secret societies of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Much as shadows cast on a wall by a fire relate only dimly to the objects whose shadows they are, but reveal their existence nonetheless, the changes that came to the Church on account of the Council recall the principles and methods developed and used by those societies. This can be seen from the example of the Italian Carbonari, whose conspiracy against the Church was revealed in a document known as ‘The Permanent Instruction of the Alta Vendita.’

Conspiracy of infiltration and subversion

The term ‘Carbonari’ means charcoal makers. Not a few secret societies of the time operated by infiltrating a craft or profession closed to outsiders and making use of its tightly-knit structures to win adherents and create a protected group identity. Charcoal-making, which required the use of inflammable substances and could be safely practiced only in secluded places, had the added advantage of providing an apt metaphor for dissent and subversion. ‘Alta Vendita’, meaning ‘high market place,’ refers to a co-ordinating body at the head of the Carbonari whose existence was probably unknown to most of the rank and file. ‘The Permanent Instruction of the Alta Vendita’ was the title given to an an anti-Catholic strategy paper which was believed to have been circulated among the different lodges of the Carbonari by the co-ordinating body.

A Carbonaro at work

While it is likely that the Carbonari originated with the Illuminati of Bavaria, they emerge into visibility only at the close of the eighteenth century, when the French revolutionary wars had spread to the Italian peninsula.

Committed to the revolutionary ideals of 1789, the Carbonari conspirators were opposed to absolutist rule, as they were to foreign rule on Italian soil. An early objective was the overthrow of the Bonapartist King of Naples, Joachim Murat. The Carbonari aspired to a unified and enfranchised Italy, which they saw as the key to the transformation of Europe, and eventually of all of humanity, into a universal fraternal republic.

The Permanent Instruction, which can be dated to the period immediately after the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815), announced a new long-term objective for the Carbonari: the seizure of the power of the Papacy by converting the Church from within to revolutionary principles. The preferred method was for agents of the conspiracy to pose as benevolent educators with orthodox Catholic beliefs. Playing on the truths generally accepted by idealistic minds, whether Catholic or not, the human passions, particularly patriotism, were to be excited in support of those forms of life which the conspirators wished to see imposed on the coming times. Of particular interest were devout Catholic families. These were the principal source of vocations to the priesthood. By mentoring young men who would later become priests, the conspirators could exert a formative influence on the future elite of the Church. Eventually, a Pope would emerge who would be tolerant of such interim revolutionary objectives as the establishment of constitutional forms of government and the creation of republican nation states.

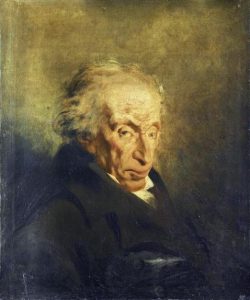

Filippo Buonarroti

The Permanent Instruction went out to the different lodges of the Carbonari in the name of Nubius, a code-name used by the supreme leader. Allegedly a high-ranking diplomat of noble descent, the figure of Nubius may have been one of the masks worn by Filippo Buonarroti (1761-1837), a man steeped in conspiracy, whom one biographer describes as the very first to make a lifelong profession out of revolution. Buonarroti was indeed a leader of the Carbonari, as he was of many other secret societies. If, as has been mooted, the Permanent Instruction was divulged to the Church by Nubius himself, who had lost out in a power struggle, it would strengthen the association of Nubius with Buonarroti. The latter, around 1833, had been forced to withdraw in favour of Giuseppe Mazzini, the founder of ‘Young Italy,’ whom he detested. Unlike Mazzini, Buonarroti did not believe that Italy was ripe for revolution.

A Pope for the conspirators

In proposing a historical model for the kind of Pope the conspirators wished to see on the papal throne, the Permanent Instruction makes a revealing comparison between Popes Alexander VI and Clement XIV. The notoriously corrupt Alexander VI would have been of no use to the conspiracy because he did not err in religious matters. Clement XIV, however, a man widely admired for his personal virtue, was a Pope according to conspiratorial requirements. As the Instruction puts it, Clement had been willing to dilute the Papal power by sharing it with secular ministers, and because of his tolerance for non-believers, he had surrendered to the opponents of the Church. For Nubius, the conciliatory approach adopted by Pope Clement towards advances in secular knowledge and the rights asserted by secular powers was the kind of religious error on which the anti-Catholic conspiracy could thrive.

Pope Clement XIV

After 1815, the Pope still ruled as an absolute monarch in his territories, the Papal States. Yet, the power of the Papacy that Nubius wished to see undermined was primarily of a moral kind. The world knew of no comparable voice that was urging men and women to live integral lives on transcendental principles and according to conscience, and had at its disposal a tried and tested body of teaching together with an appropriate disciplinary economy. The tolerance of a Pope for what was hostile to his moral authority would be destructively effective all by itself. That tolerance would eventually weaken the Papal authority and bring it to an end, but in a way that seemed natural and inevitable. Indeed, there may be no other means for the power of moral authority to be broken than to persuade him or her who possesses it to renounce it by themselves.

It is perhaps no surprise that Nubius, this enemy of Christianity, had such an exalted respect for the moral authority of the Pope. Because the Papal teaching could shape the minds and lives of the millions of Catholics all over the world, the Church was an example of the political entity which the conspirators, using different principles, and following different purposes, wished to see established. They would have denied it, but their universal fraternal community was an analogue, though a much distorted one, of the Roman Catholic Church.

The process of subversion

One can easily see where the process of infiltration and subversion would lead. Key positions in the Roman Curia and in the important dioceses of the Church would come to be staffed by individuals who sincerely believed that many secular innovations, even if they were not of Christian origin, were in the spirit of Scripture and Tradition. Scholars and theologians who could make an orthodox case for the adoption by the Church of those innovations would be encouraged in their work. At the same time, the understanding of what it means to be Catholic would be sufficiently widened so that the natural and moral sciences of the secular world would, in all but name, emerge as a third source of Divine Revelation. What had been learned from Scripture and Tradition would then require an interpretive recalibration.

In this way, by building on the commonalities between Catholic believers and non-believers of presumed good will, forms of life and expression would be established within the Church which embodied the spirit of unbelief. What the Church once deemed true of one of its more celebrated members, the Knights Templar, would become true of the Church as a whole. Believing that it was serving Christ, the Church would, in fact, serve Antichrist. The difference between 1307 and 2007 or 2037 would lie in the lack of a superordinate institutional authority with the wisdom to discern and the power to intervene.

Pope Pius IX

The exigencies faced by the Catholic Church in the 1840s provide circumstantial evidence for a process of subversion that may well have come close to success. On the death of Pope Gregory XVI in 1846, a short conclave elected the unpolitical, liberal-leaning and pastorally-minded Pope Pius IX. Confronted with revolutionary demands in the Papal States, Pius, in a conciliatory first act as Pope, declared an amnesty for political prisoners. Immediately, the new Pope was hailed as a beacon of progressive genius by populist movements which were steered by the secret societies. Mazzini himself wrote to the Pope begging him to unite Italy and to take the lead in ushering in a new era of liberty.

The assassination of Pellegrino Rossi

It appears that at this very early point in his Pontificate, Pius was preparing for a path of liberalism and tolerance in the spirit of the Permanent Instruction. In 1848, however, when revolutionary activity erupted across Europe, Pope Pius broke with his Masonic advisors and refused to commit the armies of the Papal States to a patriotic war with Austria. With the Pope’s volte face, a ‘Catholic way of revolution’ was lost. Shortly afterwards, at the opening of the Chamber of Deputies in Rome, Pellegrino Rossi, the Pope’s prime minister, was stabbed in the neck on the steps of the Palazzo della Cancelleria. Some believe that Rossi had been condemned to death by his compatriots in the secret societies for his failure to secure the Papacy for the revolutionary cause. Subsequently, the Pontificate of Pius IX, one of the longest in the history of the Church, took a course notably hostile to liberal ideas and grew more and more intransigent in the assertion of Papal supremacy in Catholic life.

On the face of it, the machinations of 1848 would have constituted a departure from the strategy set out in the Permanent Instruction. A ‘Catholic way of revolution,’ in harnessing the Papacy to a mass movement and to the limited political goals of the hour, would have gone beyond the subversion of clerical minds and the creation of a climate of tolerance for liberalism in the Church. Had the Pope followed the call of Mazzini, Garibaldi and others, and had joined in the revolution, it is likely that the Papacy would have been fundamentally altered. Its moral authority, which the original conspirators had hoped to preserve and put to use, would probably have been compromised too soon for their purposes. The temptation faced by Pius IX in 1848 thus reflects more accurately those precipitative minds which had been opposed to Nubius.

The authenticity of the Permanent Instruction

To take seriously the Permanent Instruction of the Alta Vendita, one needs to be reasonably satisfied as to its authenticity. A description of how it came to light may help towards making a judgment. Our knowledge of the Instruction is owed to the pen of one man, Jacques Crétineau-Joly (1803-1875), a well-regarded anti-liberal journalist and historian. By his own account, Crétineau-Joly was summoned to Rome in 1846 by the then Secretary of State, Cardinal Lambruschini, who entrusted to him a collection of papers dealing with the anti-Catholic activities of the secret societies. These papers, which had been in the possession of Lambruschini’s predecessor, Cardinal Bernetti, appear to have been compiled from the Vatican Archives and from contemporary police reports. In the name of the Pope, Lambruschini charged Crétineau-Joly with the task of writing a historical account of the war being waged against the Church by the secret societies. After many vicissitudes, including initial opposition from the new Pope, Pius IX, Crétineau-Joly completed his task with the publication of l’Eglise Romaine en face de la Révolution (Paris, 1859). In this influential work, the Permanent Instruction of the Alta Vendita was published for the first time, though in a French translation.

Pope Pius IX

Knowledge of the Permanent Instruction was spread more widely by two later works, The War of Anti-Christ and Christian Civilization (Dublin, London, New York, 1885) by Monsignor George F. Dillon and Le problème de l’heure présente: antagonisme de deux civilisations (Paris, Lille, 1904) by Monsignor Henri Delassus. Like Cretineau-Joly’s before him, Msgr. Dillon’s book was published with the full approbation of the Church. The colophon contains the nihil obstat and the imprimatur from the Archdiocese of Dublin, together with letters of recommendation from the highest levels of the Church, including the reigning Pope, Leo XIII. It seems that Pope Leo even arranged for an Italian translation at his own expense. Dillon included an English translation of the French version of the Permanent Instruction given by Crétineau-Joly. Crétineau-Joly’s French version was republished by Delassus, who also had the approval of the highest levels of the Church. His book is prefaced by an unusually effusive imprimatur from the Archbishop of Cambrai and by a letter of endorsement from the Secretary of State at the Vatican, Cardinal Merry del Val. The versions of the Permanent Instruction which are available in Italian today seem to derive from Crétineau-Joly, either directly, or through Dillon and Delassus.

The phalanx of official approval which accompanied these books is sometimes understood by Catholic Traditionalists as an authentication of the Permanent Instruction which possesses some kind of notarial force. It is implied that approval would never have been given if the high officials of the Church had not fully satisfied themselves that the document was genuine. While this may be true, a nihil obstat and an imprimatur confirm merely that the contents of a book are not harmful to the Catholic faith and morals and that the book may be printed and distributed. They do not have the purpose of authenticating a document. As to the additional letters of approval, these are general in scope and pertain in each case to the whole book, not specifically to the few pages given to the Permanent Instruction. Given the nature of the times, it is not unlikely that much of what had been provided to Crétineau-Joly by Cardinal Lambruschini had been procured by torture in the dungeons of the Papal States. Apart from that, his book does not shine with the meticulous listing of sources consulted which one would expect today. Undeclared scriptorial work by police agents, by Papal bureaucrats, or by Crétineau-Joly himself, cannot be ruled out. What can be said with certainty, however, is that the Church of the day believed itself to be under attack in the way described in the Instruction, and wished the Faithful to be warned.

Each of the three authors central to the public dissemination of knowledge of the Permanent Instruction, Crétineau-Joly, Dillon and Delassus, places it in the same broad historical context: History is considered the showplace of a war between Atheism and Christianity driven principally by Freemasonry, whose universalist philanthropy based on Deism and Natural Religion, erroneous to begin with, has been corrupted still further by the Illuminati of Bavaria. Freemasonry itself is believed to be Jewish in essence. In this, the authors continue a line of reasoning which seeks an explanation for the international influence of the French Revolution, and for the Hermetic and Kabbalistic symbolism used by the secret societies they saw behind it, in an alleged Jewish plot for world domination. Delassus, in particular, because of his membership of the Sodalitium Pianum, an anti-Modernist secret society of priests, looks forward to the unchristian practices of later pro-Nazi clerics. The Sodalitium Pianum employed the unsavoury techniques of spying and anonymous denunciation.

Papal authority and the Second Vatican Council

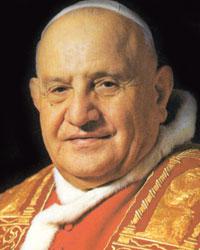

Pope John XXIII

If the authenticity of the Permanent Instruction cannot be verified to the standards of today, are the claims of a plot to infiltrate the Church and subvert the Papacy then invalid? In searching for an answer, it will prove useful to consider some of the accentuation employed by Pope John XXIII when he prepared Catholic minds for the coming of the Second Vatican Council.

In a radio address in 1962, shortly before the opening of the Council, Pope John called to mind the supremacy of his Papal office. In doing so, he referred to the Latin Christian poet, Prudentius, rather than cite from Scripture, which he could easily have done. Prudentius liked to sing of Rome as the mystical centre of Christendom due to the sustaining presence of Saints Peter and Paul, not so much on account of the authority that had been vested in them as teachers and guides, but because Rome was the place of their martyrdom. Though Pope John was undoubtedly asserting the supremacy in the Church of the See of Rome and the Petrine Office, the symbolism he used could not but weaken the association between supremacy and teaching authority in the minds of his listeners. The moral authority of the Papacy was grounded by the Pope not in the will to achieve stable and coherent doctrinal formulations which have universal validity, but in the will to offer itself in sacrifice.

It may be that Pope John wished to disentangle the moral authority of the Papacy from an antiquated idea of supremacy. It may be that the historical accretions of universal power which adhered to the Papacy because of the idea of supremacy had come to seem a hindrance to the charism of unity.

Whatever his purpose, the Council he summoned worked to dismantle the singular moral authority of the Papacy. Ideas of collegiality between Pope and bishops in the government of the Church were revived. Looking towards other faiths, the Council played down the once strong emphasis on their incompatibility with Catholicism and voted to affirm their intrinsic value. The unity of Christianity and the unity of all mankind came to be imagined as one and the same ideal.

A universal fraternal community that was not Christian, and a Pope who would lead the Church in serving its emergence, was precisely what had been envisaged by Nubius a hundred and fifty years earlier.

Whether it originated in police interrogations, the febrile imaginations of anti-semitic journalists and priests, or in the murky thoughts of Nubius, whoever he might have been, ‘The Permanent Instruction of the Alta Vendita’ anticipated to a high degree what has since become of Roman Catholicism.

Written by Eamon Kiernan

Thanks for the tip, which is much appreciated. You’ll find the mark of P2 (propaganda due) all over the events that destabilised Italy in the 1970s and early 1980s, the atrocities of the Red Brigades, for example, which appear to have been false flag operations steered from within P2. A supposedly ‘irregular’ Masonic Lodge, P2 brought together high-ranking politicians, military leaders, industrialists, and so on, in a kind of permanent Fascist conspiracy. There was also a Vatican connection, which you can see from the Sindona and Calvi affairs. P2 was suppressed in 1982 amid great scandal, but it might not have gone away. The original reason for the foundation of P2 within the Grand Orient of Italy in the late nineteenth century was to oppose the Church, so P2 can be counted as one of the successors of the Carbonari of the Alta Vendita. If I come across anything, I’ll post it here.