By Eamon Kiernan

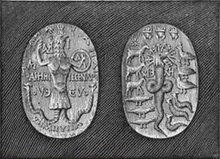

An Abraxas gemstone

Abraxas, the presiding deity of Demian, is well known to antiquarians and students of Gnosticism. Often found on carved stones dating from the early Christian era, ‘Abraxas’ or ‘Abrasax’ commonly appears as a being with a human torso, the head of a fowl and the legs of a serpent, carrying a shield and a whip.

This deity is closely associated with the Gnosticism of Basilides, who taught in Alexandria in the first half of the second century AD. In his reconstruction of Basilides’ system of cosmogenesis, G. R. S. Mead, a Theosophist, assigned Abraxas to a position at the apex of the world of the senses. Here, Abraxas serves as the ruler of “elemental forces which fashion the body […] the lowest servants of the karmic law.” [1]

The purpose of the carved stones was to work magic. The purpose of Basilides’ Gnostic system was to map out a universal theory of reality. One modern Westerner who engaged intensively and fruitfully with Gnosticism was the Swiss psychiatrist, C. G. Jung. In early 1916, a powerful visionary experience led Jung to identify himself with Basilides and to compose a series of instructions to ‘the dead’ in the name of the Gnostic teacher: the Septem Sermones ad Mortuos und Basilides. First written down in the journals known as the ‘Black Books’, Jung soon had the Septem Sermones printed in a limited private edition, the exemplars of which he gave as presents to a restricted circle of friends. In this enigmatic work, Abraxas plays a prominent role.

Also in 1916, Hermann Hesse began a course of psychotherapeutic treatment with Jung’s Lucerne collaborator, Josef Bernhard Lang, which lasted for eighteen months. In late 1916, Hesse read Jung’s Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido, which offered what was then the standard account of a key Jungian postulate, the process of Individuation. Hesse judged it to be a work of genius. In the autumn of 1917, while he was still working on Demian, Hesse had dinner with Jung in a Berne hotel, during which, as his diary records, the conversation turned to Gnosticism. Though in later life Hesse would write disparagingly of Jung’s work, as of all forms of depth psychology, at the time in question, his remarks on Jung’s person and ideas were wholly positive.

The excitement surrounding Jung’s discovery of Abraxas can by gleaned from the astonishing rapidity with which this Gnostic figure entered his analytical sessions and those of his followers. Evidence for this is provided by the diary of Fanny Bowditch Katz, an American patient of both Jung and Jung’s then assistant, Maria Moltzer, who was also a friend of J. B. Lang. Katz noted in 1916 that Moltzer had introduced her to some of Jung’s “new ideas of God”, among them, Abraxas. Her diary gives a helpful summary of the principal characteristics of this figure: “‘Abraxas’, the Urlibido […] the individual force […] the one power [behind the dualism] of God embracing the devil […] the great cosmic force behind each God”. [2] Almost certainly, J. B. Lang was drawing on the same new ideas in his analytical sessions with Hesse.

C. G. Jung liked to claim that Hesse’s Demian owed a great deal to his work. Though there are clear affinities between Jung’s thought and the ideation of the novel, Hesse would have come across Abraxas independently of Jung, at least as early as 1895-1896, when he was studying the works of J. W. von Goethe. The poem ‘Segenspfänder’ in Goethe’s West-östlicher Divan makes use of Abraxas in the magical meaning. In this poem, Goethe’s Singer, addressing the use of talismans and amulets, refers to Abraxas as a reserved, rarely-used power, a caricature of the highest God, associated with madness and absurdity. The connotations of rarity and disorder reappear in Demian, which describes Abraxas as a “forgotten” God associated with the protagonist’s growing ability to cross conventional moral boundaries.

While Goethe may have provided Hesse with an outline meaning for Abraxas, the more elaborate portrayal in Demian also shows close parallels to Jung’s description of the deity in the Septem Sermones.

In the second of the Septem Sermones. Abraxas is introduced as a ‘God’ whose nature is ‘effectiveness’. Abraxas stands above and behind God and the Devil, who are described as ‘effective fullness’ and ‘effective void’, respectively. There follows a section of hymnic praise of the creative-destructive power of Abraxas. According to the version published much later in Jung’s Red Book, Abraxas is the “[ruler of] the bodily juices, the spirit of sperm and the entrails, of the genitals […] of the joints […] of the nerves and the brain […] the spirit of the sputum and of excretions”. He is both “vital force” and “sucking gorge of emptiness”, who produces truth and lying, good and evil, light and darkness, life and death in the same word and in the same act. Abraxas, Jung concludes, not without admiration, “is terrible”. [3]

These sentiments are echoed in Demian by the failed priest, Pistorius, who instructs the protagonist in the ‘worship’ of Abraxas.

Scholars have noted the correspondences between Jung’s account of Individuation and the coming-of-age of Emil Sinclair. [4] According to Jung, Individuation cannot succeed without Abraxas, because the power of the ‘God’ gives effect to each member of a pair of opposites. At the same time, it is the task of the emerging individual to become free of Abraxas. This is done by living the opposing qualities to the full, thereby achieving a sustainable balance of personality.

Hesse, however, was never a disciple of C. G. Jung, and his treatment of Abraxas differs somewhat from Jung’s. I hope to deal with this more fully in a later contribution.

_____________________

[1] G. R. S. Mead, Fragments of a Faith Forgotten. Some short sketches among the Gnostics mainly of the first two centuries. A contribution to the study of Christian origins, based on the most recently recovered materials. (London; Benares: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1900), 281.

[2] Quoted in Sonu Shamdasani, “From Neurosis to a New Cure of Souls: C.G. Jungʼs Remaking of the Psychotherapeutic Patient,” Medical Humanity and Inhumanity in the German-Speaking World. Edited by Mererid Puw Davies and Sonu Shamdasani. (London: UCL Press. 2020), 29.

[3] Quoted in Ann Belford Ulanov, “Encountering Jung Being Encountered,” Jung Journal: Culture & Psyche, Vol. 5, No. 3 (Summer 2011): 59.

[4] See, for example: David G. Richards, The Hero’s Quest for the Self: An Archetypal Approach to Hesse’s ‘Demian’ and other Novels.( Lanham, Md: University Press of America, 1987).