The Swiss psychiatrist, Carl Gustav Jung, straddled an uneasy divide between science and mysticism. He was a prolific writer, if not always a clear one. One of his most enigmatic texts carries the title Septem Sermones ad Mortuos and Basilides (Seven Sermons to the Dead and Basilides). A mythical-mystical outpouring replete with Gnostic allusions, it emerged during a long series of visions which began in 1913, around the time of his break with Freud. It was kept private until after his death. Jungians see in Septem Sermones the prefiguration of all of the master’s later work. What strikes me most of all is its nihilism.

C. G. Jung, ca. 1913

In seven short discourses, Basilides instructs the dead on the nature of reality and on man’s place in it. Sermo 1 establishes the relation between Pleroma and Creatura as the basic pattern of cosmic reality. The nature of Pleroma is fullness and emptiness. The nature of Creatura is distinctiveness. The task of human beings as exemplars of Creatura is to distinguish themselves from Pleroma by enabling qualities to become distinct and by then making themselves distinct from those qualities. The qualities appear to the human mind as pairs of opposites. Basilides explains that a man should not strive for the qualities represented to him in his thoughts, for this would cause him to lose himself to Pleroma. He must strive for his being alone.

Sermo 2 states that God and the Devil are not Pleroma but Creatura. God and the Devil are described as ‘effective fullness’ and ‘effective void’, respectively. Here, a God behind God and the Devil is introduced, Abraxas. His nature is effectiveness. It is through Abraxas that the fullness and the void become effective. It is man’s task to distinguish God from Pleroma, otherwise effective fullness is lost to man. Distinguishing God cannot be done without distinguishing the Devil. Later, in Sermo 7, we read that distinguishing God means distinguishing an individualised God as the goal of a single human life, which can only be accomplished if the man also distinguishes himself from Abraxas. Sermo 3 states that it is from Abraxas that man draws life. The power of Abraxas is such that that in any one act, both good and evil become effective. Abraxas is therefore ‘the operation of distinctiveness’ and the driving force behind man’s distinguishing of himself and his God from Pleroma.

Sermo 4 insists that God is not a single category, but a multiple one. Four principal Gods are mentioned, God-Sun, called the One, who is the beginning; Eros, called the Two, who binds together and spreads himself as brightness; the Tree of Life, called the Three, who fills space with bodily forms; and the Devil, called the Four, who opens what is closed and dissolves what is formed of bodily nature. Basilides counsels against making one God out of the many, because by this, Creatura, whose nature and aim are distinctiveness, suffers mutilation.

Sermones 5, 6, 7, deal with the relations between Gods, Man, spirituality and sexuality. Sermo 6 restates the position that Abraxas, like all the Gods, is both a task to be completed and a danger to be faced. Lastly, Sermo 7, as mentioned, presents the individual man in relation to his goal and his personal God, called here his Star. Abraxas figures now as the ‘creator and destroyer of his own world’, from which the man must turn away. This personal goal of life that is also a God has a multi-aspectual character: to one man a Star, in its own world it is Abraxas.

Why do I think this is nihilism? It is Jung’s purpose, through Basilides, or possibly the purpose of ‘Basilides’ through Jung, to correct and supplant the traditional narrative of Christianity. But what he ends up with is no more than a set of echoes of the Christian narrative reconfigured in an impoverished imagination.

Against the Christian conception of the one God who is good, who is personal, and who is the creator of all things seen and unseen, Basilides sets ‘Pleroma’, which is impersonal, is not good, and does not create. Life for a Christian is a call by God to learn to love Him and serve Him. For Basilides, life seems to be a cosmic poker game. The players are lost souls blinded by effectivity. They try to bluff Pleroma in order to stay alive.

Here’s why:

The mission of Basilides

Basilides speaks to the dead only because they have returned from Jerusalem dissatisfied. If you ask me, the dead had no business going to Jerusalem. If they returned from there dissatisfied, it is because they had gone wrong to begin with. Basilides now pours his alternative teaching into their resentful ears. He is a liar. What he wants to do is to hide from the dead the nature of their wrongness and to make it all the more improbable that in the wasteland in which they find themselves they will find a remedy. The lies he tells are designed to persuade them, against all the evidence, that the wasteland is not a wasteland, but a thriving paradise.

Pleroma and Creatura

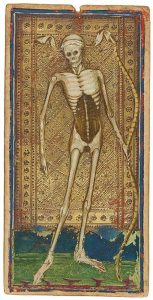

‘Death’. Milan, ca.1450.

Visconti-Sforza Tarot.

(Morgan Library)

If you take the Christian God and you cancel out His personhood and His goodness, declaring that for you they do not exist, and that all the signs of them in Creation are signs of something else, you may well end up with something like Pleroma and Creatura. It is like stripping face and flesh away from a flourishing person and laying bare the skeleton, to declare the dead bones to be that person’s reality.

Qualities come in opposites

If the qualities created in goodness by God are not available to you as a gift from God, because you refuse to accept gifts from God, you may decide that you want to live, anyway. To do this, you will somehow have to avail of the qualities, because there is no other way to live. Then, you will need to steal them. This can be done by forming an analogue of creation in your mind. Because what you start with is itself an analogue, you are therefore making an analogue of an analogue, but without the help of God given by Grace and Revelation. You might not see the wood for the trees. You might not see the trees at all, only vague shapes in the dimness.

To make your new representations of the qualities real, you would give your love to them and energise them, using whatever vitality is left to you. As you exercise your analogue of creation, you are all the time depending on the Good God you refuse to believe in to sustain you in being. If you can make opposites out of qualities that are not in themselves opposites, and they become real for you, there is a reaction, something like an explosion. This gives you energy without you having to admit that the energy is from God. At the same time, the qualities are reshaped in your analogue of creation. The original relations of subordination and service between qualities become disrelations of opposition and conflict.

Abraxas is the God of effectiveness

Abraxas is the name Jung’s Basilides gives to the power of effectiveness as its own law. The historical Basilides, a Gnostic who taught in Alexandria in the second century AD, may have given a somewhat different meaning to Abraxas. Not enough is known about him to make a proper comparison. The effectiveness of Abraxas operates outside the laws that express the goodness of God, even if it may sometimes seem to coincide with those laws. It is not likely that Abraxas can have an existence independent of the one you give him in your analogue of creation. His property of making qualities real serves to mask his true nature. Abraxas may be the ‘God’ of effectiveness, but not of right effectiveness. He is the ruler of transgression and excess.

A man must strive for his being alone

If you follow Jung’s Basilides, you live inside your own mind. Inside your mind, your being, that is, your self, can easily become an object of your striving, your admiration, your love. You call on Abraxas to make your opposites real so that you can distinguish yourself as yourself from qualities. This is striving for your being. The more you do this, the more you separate yourself from the ordered flourishing of the cosmos all around you, and the more curved in on yourself you become. Eventually, it occurs to you that it is you, in fact, who are God. After all, you are now self-generated. You will seek to preserve for ever that moment of sublime self-recognition of Godself against the pull of dissolution. This will become your sole task. But you will not succeed. The lamp that is you will run out of oil, the analogue of creation will fade to nothing, and the moment of self-recognition will pass.

It would perhaps be a mercy if at that instant you were to pass, too. What would remain for you to look at, assuming you are still able to see? What is the likeness of an existence that has failed utterly and conclusively?

This false path began with the mental replacement of God and His good creation by Pleroma and Creatura. It continued with the mental replacement of a life promised to the loving, obedient service of God by a life of willed individualisation of self.

“But I want to live,” you might say, and all the dead with you. “I want to live as myself. This is what I have to do.”

No, it is not.

Consider these lines of poetry:

Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

[…]

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

They are from ‘Pied Beauty’ by Gerard Manley Hopkins.

What strikes me is their gratitude.