Five hundred years ago, the German religious reformer, Martin Luther, confronted the awesome power of the Roman Church, and discovered that he was free. At the same time, he discovered that every Christian is free, because freedom is what is taught by the Gospel of Jesus Christ. His argument is presented in the Tract, On the Freedom of a Christian.

The following is an attempt by an interested non-specialist, myself, to read this work and consider some of its meaning.

Luther’s Tract on Freedom

‘On the Freedom of a Christian’ (Von der Freyheyt eynisz Christen menschen) was written as a public response to the Bull of Leo X, Exsurge Domine, which threatened Luther with excommunication. It exists in a German and in a Latin version, which differ from each other in places, but not significantly. The Latin version was sent to Pope Leo late in 1520, together with a long letter of dedication and explanation.

I follow the German text from the definitive Weimarer Ausgabe, but make reference to the Latin where necessary.

By 1520, Luther was determined not to abandon the anti-Papal theological positions he had arrived at through hard questioning and careful research. Strangely, his accompanying letter to the Pope often strikes a respectful, even filial tone. Pope Leo is addressed as ‘father’ and Luther declares himself to be his ‘friend’ and ‘most humble subject.’ The theological controversy that now separates them he blames on malignant papal advisors who have misrepresented his positions. Using the example of Saint Bernard and Pope Eugene III, he claims that his attacks on the papacy are motivated by the same spirit of fraternal correction that had moved Saint Bernard in his public admonitions of that erring pope. Luther calls on Pope Leo to free himself from the evil tempters who wrongly exalt him over other Christians and expresses confidence that if he could plead his case before Leo in person, the present controversy would easily be settled by Leo himself.

Then, in December, 1520, shortly after finishing the Tract, Luther joined in a public burning of books of theology in Wittenberg, and threw to the flames a copy of Exsurge Domine. Luther’s assurance of respect for the person of the Pope was coupled with the complete repudiation of his papal authority. A resounding paradox.

Luther burns the Papal Bull

Paradox is crucial to Luther’s views on Christian freedom, as it is to his views on the nature of God and Man. The Christian is free and is lord over all things. [1] This is how the German version of the Tract begins. It is immediately followed by its contradiction. The Christian is a slave and is subject to all things. [2] The paradox propels us with force on a journey which would not be possible without it. Luther’s point is that a Christian is free because he is a Christian, and for no other reason, and that he is free only in a Christian kind of way. Commendably, Luther gives his references. All that he writes in the Tract is nicely backed up from Saint Paul, with chapter and verse supplied for anyone who wants to go and check for himself. Precisely this is reckoned as one of Luther’s achievements. He encouraged ordinary people to go and see for themselves what is in the Bible rather than take at face value what comes from the professionals. When I check out Saint Paul for myself, though, I don’t always find the same meanings that Luther found. But we’ll leave that aside.

The word Luther uses for a Christian is ‘Christen mensch’ (Christian man or woman). A customary enough term in Luther’s time, it is unusual today. It is also quite useful. It does not allow us to think about the idea of a Christian without the idea of a man. It emphasises more strongly than we might be accustomed to that a Christian man is not a natural man. A Christian is not born, he is made.

For Luther, a Christian is made by Baptism. Through the sacramental use of water and prayer, a foundational supernatural gift is imparted. In this Tract, Luther is more concerned with what follows Baptism. In Section 7, he writes of “forming the word and Christ inside one” [3] and declares, strikingly, that it is the only ‘good work’ that a man or woman is capable of doing. It was ‘good works’, we remember, that first roused Luther against the Church of his day, and transformed the obedient Augustinian friar into a “wild boar from the forest”, to use the words of Leo X. Before examining ‘good works’ more closely, a certain emphasis may be noted. For Luther, this work of formation, the one ‘good work’ that is within human capacity to do, seems to be something that the Christian does to himself, or herself. Competent people may be around to help, but it seems that Luther expects the Christian to form the word and Christ inside himself by himself. Presumably the Christian will have his Bible open in front of him, but in his formational encounter with Christ, he is unbeholden to any third party. This, of course, is the early Luther. It did not take long for the Reformers to set up their own dogmas and institutions and begin to enforce conformity. But here, at the very beginning of the Reformation, Luther had a clear vision of freedom from human authority that he thought was fundamental to being a Christian.

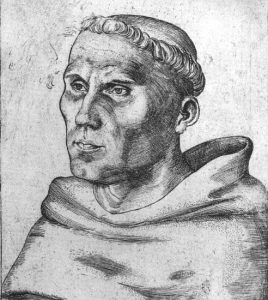

Martin Luther in 1520

Drawn by Lucas Cranach d.Ä.

Now to ‘good works’. Elsewhere, Luther wrote that works are good if God has commanded them and if they are performed out of Christian faith. In this Tract, much space is given to Luther’s rejection of works that are falsely believed to be good. Various examples are mentioned: fasting, pilgrimages, endowing monasteries, even prescribed prayers, meditation and contemplation. These are at best a waste of time. They may even be blasphemous. Luther points out that it is not works themselves he objects to, but the false belief that works can bring about the justification of a sinful man before God.

A term like ‘justification’ needs to be checked in the reference books. This is what the old Catholic Encyclopedia has to say: “[Justification:] A biblio-ecclesiastical term; which denotes the transforming of the sinner from the state of unrighteousness to the state of holiness and sonship of God.” [4] For Luther, as for most Christians before and after him, the relationship between God and Man could best be understood through the analogy of law and punishment. Man is a criminal. Damnation to Hell is inevitable, unless there is a divine intervention. This intervention took place through the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Jesus, which needs to be applied to an individual life through the action of faith.

As Luther saw it, a Christian is dual-natured. There is the inner man of faith, and the outer man, who is of sin. To these two natures correspond two contrary wills. The will of the inner man is to serve God. The will of the outer man is bent on doing evil and wages perpetual war on the inner man. Works, because they pertain to the outer man, are governed by this contrary will and are unavoidably sinful. Because a life without works is impossible, it is almost impossible not to commit sin.

In Luther’s theory of Justification, the sins of a Christian are taken from him by Christ, who takes on those sins as his own property, as if he had committed them himself. This Christ did in advance, through His crucifixion. Because of this great sacrifice, the righteousness of Christ is gifted to the individual Christian. In Section 12 of the Tract, Luther calls this process a “happy exchange”. [5] Faith is likened to a marriage between Christ and the soul by which the believer and Christ exchange the goods they possess. Because all that the soul-bride possesses is sin, this toxic dowry is assumed by Christ and destroyed. In a Baptismal analogy, Luther imagines a sinner’s sins being drowned in Christ like in water. [6] The effect on the soul-bride is permanent. The next time she sins, that new sin is immediately destroyed by the righteousness of Christ now living in her.

Luther in 1520

Lucas Cranach d.Ä

Again, this is the early Luther. After his final break with the Roman Church, the reforming doctor seems to have moved towards a more formal, and a bleaker, view of Justification. In place of a repeated Baptismal washing of his being as he goes through life, the sinning Christian receives from God merely the ascription of the righteousness of Christ, which takes away not the sin, but the juridical guilt of the sinner. In this later view, the human burden of the trangression remains in the life with all its ruinous force.

To my mind, Luther’s earlier view is superior. Righteousness appears to be identical to the living spirit of Jesus dwelling within the soul of the believer. It is another word for His love. The gift of Christ is therefore really and truly given and can exert a transforming power on the life. In the later view, the gift does not seem to be existentially given. It is held in trust, so to speak, until after death. It remains external to the person. The transformation of the life, if it can be accomplished at all, takes place at a greater distance from Christ, by means of heroic acts of the will and a more or less blind exertion. Given that Luther found a source for his theology in his own subjective experience of faith, the progress of the Reformation may not have brought him closer to God.

Sections 19-25 of the Tract strongly assert the earlier, brighter note. Through the practice of faith, the inner man can learn to bring the outer man under his control. Works can then be done out of an unselfish love of God. An ideal state is revealed in which all a man’s doings, because of his constant increase in faith, become good, and the man or woman dwells unselfishly in love as the free servant of all, as Jesus taught his disciples to do. Human life on earth approaches once again the perfect life of Paradise before the Fall.

Sin boldly, Luther later wrote to his friend, Melanchthon. His words suggest that because a Christian has no choice but to sin, he or she should sin fearlessly, with confidence in Jesus Christ. If the sin, in the form of the work, is done with enthusiasm and commitment, and is thus done well, it can assist the growth of the person. Perhaps from there it can contribute to deeper repentence. If that is what Luther meant, there is great freedom in it. But it comes at a price. Sin is easily mistaken for a constituent element in human life which is necessary to being fully human. Sin easily presents itself as a tragic destiny which lies outside anyone’s responsibility, rather than as a discrete act or set of acts which I freely chose, but need not choose again. One could take from the Bible and from Christian tradition a less totalising and a less deterministic view.

Fundamentally, Luther’s paradoxical freedom of a Christian turns on freedom from the fear of damnation. That is what he took from Saint Paul. That is what he believed to be validated in his experience of being a Christian. Narrowly one-dimensional though it is, it seems right as far as it goes. An informed Christian well knows that he is worthy of punishment in Hell for all eternity and that his rescue by Jesus Christ is a free gift and wholly undeserved. But he also knows that the gift is given, and that he needs only to accept it and make use of it. A Christian, therefore, always has reason to hope. This holds the potential for turning to the good all experiences of failure, great and small. A man radically affirmed by God, as a Christian is, knows himself empowered, in his small way, to affirm as God’s whatever he meets with on his path, good or bad. This has the potential to free the persons and things he encounters from violation and exploitation.

Such is that paradoxical being, the Christian. He stands in contradiction to himself and to the world he finds himself in. Because of this, he is not only free, he is also a liberator.

[1] “Eyn Christen mensch ist eyn freyer herr über alle ding und niemandt unterthan” WA 7, S. 21.

[2] “Eyn Christen mensch ist eyn dienstpar knecht aller ding und yderman unterthan” WA 7, S. 21.

[3] “Drumb solt das billich aller Christen eynigs werck und übung seyn, das sie das wort und Christum wol ynn sich bildeten, solchen glauben stetig ubeten und sterckten. Denn keyn ander werck mag eynen Christen machen […]” WA 7, S. 23.

[4] Pohle, Joseph. “Justification.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 31 Dec. 2020 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08573a.htm>

[5] “[…] der frölich wechßel und streytt […]” WA 7, S. 26.

[6] “[…] ßo er denn der glaubigen seelen fund durch yhren braudtring, das ist der glaub, ym selbs eygen macht und nit anders thut, denn als hett er sie gethan, ßo mussen die sund ynn yhm vorschlundenn und erseufft werden […]” WA 7, S. 26-27.