We have them in the family, in the neighbourhood. We used to know them at school. People who chose the wrong professions, if they chose at all, and were not simply pushed around by force of circumstances. Chance puts them beside us, and when the going gets rough, they just throw in the towel and go home.

They are the duffers and ditherers, the people who never do things properly, who seem unable to stand upright in their lives. We remember a gift they once had, a shining enthusiasm, a little something special that in better days had marked them out with promise, and we wonder why they could not make more of it.

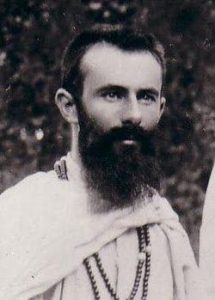

With such a person these lines are concerned. His name is Maurice Bellière.

Abbé Maurice Bellière

Maurice was a French Catholic priest who belonged to the Society of the Missionaries of Africa, more commonly known as the White Fathers. In 1905, after a few years of reliable service on the African Missions, Maurice ran away and returned to France. He died in an asylum for the insane in Caen in 1907. He was 33.

Maurice was by no means only a duffer, but an unmistakeable cloud of failure hangs over his life. A strange military air wafts from it: dereliction of duty, insubordination, cowardice. This was a time when French missionaries served France as well as the Church, when French colonial forces helped to determine mission strategy, and French intelligence services asked for and received regular reports from Catholic mission stations in far away places.

At first, Maurice had studied for the priesthood at the diocesan seminary in Sommervieu, near Bayeux. Barely able for the demands of his training, he wrote to the superior of a nearby convent of Carmelite nuns to ask if a member of the community could be assigned to pray for the success of his vocation. The task fell to Sister Thérèse.

A deeply afflicted young woman, though one would not have noticed it because of her joyful demeanour, Sister Thérèse did not allow her sufferings to distract her for as much as a moment from what she took to be her duty. She was assailed not only by the tuberculosis in her body but also by the demons of the spirit. As she drew closer to bodily death, she also approached that death of the mind and heart that is despair. She breathed not a word of her torments, unless required to by religious obedience. In a triumph of loving faith, she routed her spiritual assailants. We know her today as Saint Thérèse of Lisieux.

Sister Thérèse adopted the dreamy and vacillating Maurice as her little brother. For about a year, she prayed incessantly for him, offered her sufferings for him, and corresponded with him, addressing the often trivial issues he raised in his letters, and putting before him elements of the new way to God she had discovered, the so-called ‘little way’ of confidence and love. The last letters she wrote to him were wrestled from an abyss of agony and exhaustion, but they give hardly a sign of it. Beautifully worded, they focus completely on the young man’s needs, and they shine with insight, encouragement, affection and good advice. The day she died, 30th September, 1897, was the day the newly-ordained Father Maurice departed for Africa and the missionary life.

To the present writer, who prefers a man to succeed rather than fail, the story of Fr. Maurice Bellière throws a rather puzzling light on Saint Thérèse. Had she not offered her life as a Carmelite nun for missionary priests? Had she not promised to return after her death to spend her heaven doing good in this human world? Yet, here is a missionary priest, one personally known to Saint Thérèse, a priest to whom she had directly promised her unfailing assistance, a priest, moreover, of whose sincerity and commitment there can be no doubt, and he turns out to be a failure. Given such assistance, one would imagine that he should have done better.

At first, Maurice had fared well in his missionary postings. Because of his knowledge of English, he spent a fruitful year in Algiers as the secretary to Bishop Léon Livinhac, who became a friend. Later, Maurice was sent to a mission station in Nyassa as its superior. These were positions of trust, and Maurice filled them competently enough. Nyassa, though, was unhealthy country for Europeans. Exposed as he was to the tsetse fly, Maurice may have been infected with sleeping sickness, which causes mental deterioration before it kills. This would explain his increasingly erratic behaviour and his early death.

It is no less possible, however, that the destructive force that crashed in on Maurice, leaving him permanently untethered, was Bishop Dupont.

Bishop Joseph Dupont

Joseph Dupont, Vicar Apostolic of Nyassa from 1897 to 1928, is a legend among African missionaries. Strong and fearless in his confrontations with the rival colonial powers of Germany and England, he was equally impressive in his dealings with hostile tribal chiefs. A compassionate man, he had gained the respect and the trust of many through his care for the sick and through his advocacy work on behalf of victims of slavery and other injustices. When he first appeared among them, the Bemba peoples of the region had associated him with the legendary White Messiah of their mythology. After their conversion to Christianity, they gave him an honorary name, Bwana Moto Moto (meaning Master Fire Fire), and they made him for a time their chief. In 2000, due to popular demand, his mortal remains were repatriated to Chilubula in present-day Zambia, the site of his first mission station, and given a hero’s funeral.

A former soldier, Bishop Dupont expected military standards of operational efficiency to prevail in his apostolic territory. In 1905, when he returned to Nyassa after some years in France, the bishop chose Maurice Bellière to act as his secretary and companion on an inspection tour of mission stations. Gifted with almost superhuman powers of endurance, he demanded the impossible from his subordinates, Maurice included. He does not seem to have made a difference between obedience out of love and obedience out of fear. Maurice may well have dissented from the Bishop’s understanding of the task and role of the missionary. If he did, he is not likely to have been given a hearing. When his assignment was over, Maurice absented himself without permission, to reappear in France some months later, a physical and mental wreck.

Unfortunately, Maurice Bellière was an unfathered man. His mother had died when he was an infant, and his natural father had placed him in the care of his wife’s sister and her husband, and had left the family, never to return. Maurice was brought up in a loving environment, but the truth of his parentage was kept from him. It was quite a shock to the growing boy when he discovered that he had a natural father who was still alive. Maurice uncovered his father’s Paris address and set out for the French capital in the hope of a cordial reunion, only to be rebuffed.

Parental figures are never merely parents; they remain constellations in the mind that channel psychic energies in formative ways. Some psychologists have written of the father-imago as a largely unconscious complex of meanings which can have a strong positive or negative effect on a person’s development and well-being.

One can imagine the sense of emergency that must have taken hold of Maurice as he accompanied Bishop Dupont from one poorly performing mission station to another. A religious superior, in some respects, was a father to his priests, but this superior was stomping around the lives of his subordinates like the father from Hell. At some point, the father imago and the fiery and fearsome bishop must have fused in Maurice’s psyche. The merciless being who had first abandoned him had returned. And he possessed the unchallengeable power to shock Maurice’s mind into conformity with his own and bulldoze him with his peremptory needs. A bishop, in some respects, stood in the place of God, and Maurice must have found himself caught up in a desperate mental struggle. Forced to choose between the God of Merciful Love and Bishop Dupont, he could have seen no alternative but to run away.

Saint Thérèse of Lisieux

This brings us back to Sister Thérèse. Writing on July 18, 1897, she told Maurice what he could expect from her after her death:

“When I shall have come into port, I shall teach you, dear little brother of my soul, how you must sail the stormy sea of the world, with the abandon and love of a child who knows that his Father cherishes him, and would never think of leaving him alone in the hour of danger.”

Can Saint Thérèse have kept her promise?

It is true that Maurice continued to serve at the side of Bishop Dupont until his tour of duty was completed. His perseverance, though it represents only the bare minimum for a missionary, seems remarkable under the circumstances. A Catholic would readily see in it the supernatural assistance of Saint Thérèse. But it did not enable a change for the better in Maurice’s painful circumstances, nor did it prevent the final break with the bishop which cost him his good standing with his Society.

To refuse obedience and abandon one’s post was no small matter for a priest imbued with reverence for duty and ecclesiastical authority. Saint Thérèse may well have stiffened his resolve. If she did, there is a potentially subversive quality to her guidance that does not sit easily with how a saint is usually perceived. Such unboundedness was certainly in her character. As a young girl, when the local superiors had refused to allow her to become a nun before the usual age, she importuned the Pope to overrule them. She had a strong, unashamed desire to be a priest, an impossibility for a woman. Some of her more challenging statements were edited after her death to set a safe limit to their radicality.

It would seem that the Church, discomfited by her holiness, preferred to press her into the usual mould and uphold its complacency. Saint Thérèse would not have wanted Maurice to become a priest of that kind. Not for her a paper figure eager to show how good he is to his superiors while his heart stays small.

Maurice’s irregular status must have deprived him of the usual official documents and also of money and protection. That he could travel safely from Nyassa to France in such unlikely circumstances suggests once more that he was receiving supernatural help. We may note that during the First World War, many French soldiers turned to Thérèse of Lisieux, who had become more widely known, though her cult had not yet been approved by the Church. Some of those who came through the hell of the trenches remained convinced to their dying day that they had received help from her in dire need.

Saint Thérèse of Lisieux

But it is in a more fundamental sense, one going deeper than the assurance of personal safety, that Saint Thérèse kept her promise to Maurice Bellière. The ‘abandon and love of a child’ takes on a new meaning when the father imago has turned malignant, when the conventional social and religious structures are breaking up, when one’s natural strength is lost to illness, and no further attempt can be made to build a life.

Here, a new spirit is required. There is a taste of it in a prayer Maurice received in a letter from his spiritual sister:

“I ask of you, O Jesus, a heart that loves you, a heart that cannot be overcome, prepared to resume the fight after each storm, a heart that is free and does not allow itself to be seduced, a heart that is straight and does not follow crooked ways.”

Would it have been a surrender to a seduction of the heart if Maurice had stayed on the missions and tried to become more like Bishop Dupont? Would it have made him crooked to conform to the God of Fear, who was so unlike the God of Love he had learned about from Saint Thérèse? It seems so.

Maurice failed in his duties as a missionary priest. But what does it matter? Failure in externals may have been the only path still open for a heart determined to be free of false Gods.

When the going got rough, Maurice Bellière threw in the towel and went home. Drifting in and out of madness, his dreams in ruins, his death creeping up on him, a miraculous new opportunity was offered to him. In his suffering, he could join with Saint Thérèse and with Jesus Christ in sacrifice and in triumph.

In one of her letters to Maurice, Thérèse had stated that for her little brother there could be no half measures, he would have to become a saint.

In the failure of his life, she was surely there to show him the way.

Note:

My source for the life of Abbé Bellière and for the quotations from the letters of Saint Thérèse is Maurice and Thérèse: The Story of a Love, by Patrick Ahern (New York, 1998).

My source for the life of Bishop Dupont is Remembering Bishop Joseph Dupont (1850-1930) in Present-Day Zambia, by Marja Hinfelaar, published in the Journal of Religion in Africa, (Vol. 33, November, 2003).

The rather speculative interpretations are my own.

EK

May, 2020